Historically, client-side discoverable credentials have been known as resident credentials or resident keys. Due to the phrases ResidentKey and residentKey being widely used in both the WebAuthn API and also in the Authenticator Model (e.g., in dictionary member names, algorithm variable names, and operation parameters) the usage of resident within their names has not been changed for backwards compatibility purposes. Also, the term resident key is defined here as equivalent to a client-side discoverable credential.What does this mean exactly?

- “resident” credentials and “discoverable” credentials are the same

- “non-resident” credentials and “non-discoverable” credentials are the same.

Discoverable credentials

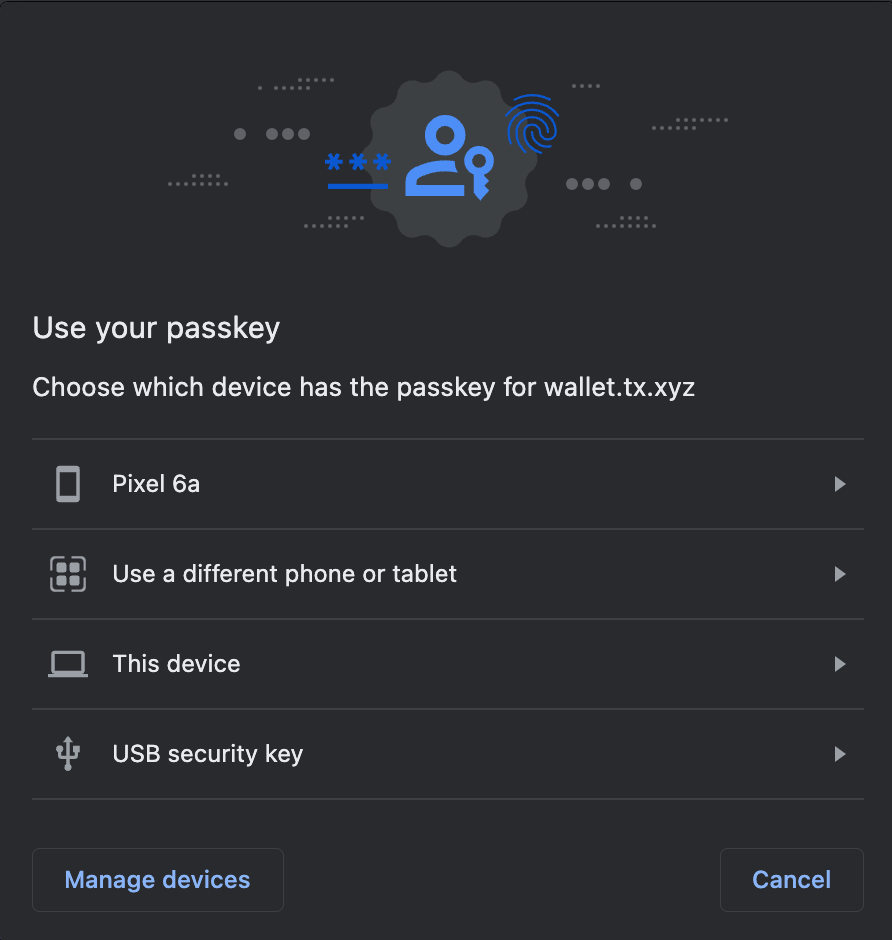

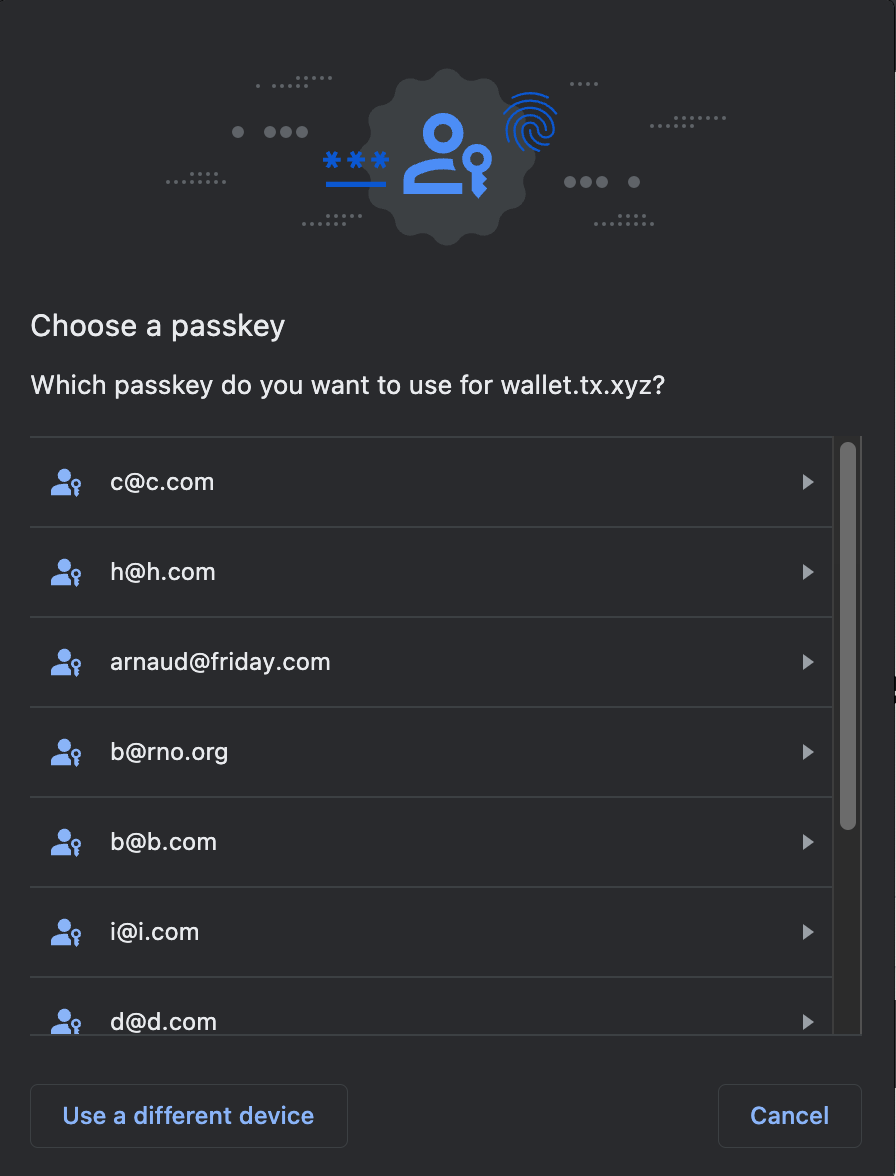

A discoverable credential is a self-contained key pair, stored on the end-user’s device. Discoverable credentials are preferred because keys are self-contained, can easily be synced and can be used across devices independently. Crucially for UX, the end-user is able to list their passkeys and choose which device/passkey they’d like to use:

Non-Discoverable credentials

A non-discoverable credential isn’t stored on the end-user’s device fully: Turnkey must store the generated credential ID; otherwise the user won’t be able to sign. This is because the actual signing key is a combination of an “on-device” secret and the credential ID (see details here). Why would you choose non-discoverable credentials?- Most hardware security keys have limited slots to store discoverable credentials, or will refuse to create new discoverable credentials on the hardware altogether. YubiKey 5 advertises 25 slots, SoloKeys support 50, NitroKeys 3 support 10. Non-discoverable credentials aren’t subject to these limits because they work off of a single hardware secret.

- Security keys can only allow clearing of individual slots if they support CTAP 2.1. This is described in this blog post. When security keys do not support CTAP 2.1, slots can only be freed up by resetting the hardware entirely, erasing all secrets at once.

- Non-discoverable credentials take less space. This is important in some environments, but unlikely to be relevant if your users are storing passkeys in their Google or Apple accounts (plenty of space available there!)

- Credential IDs have to be communicated during authentication (via the

allowCredentialsfield). This allows browsers to offer better, more tailored prompts in some cases. For example: if the list contains a single authenticator with"transports": ["AUTHENTICATOR_TRANSPORT_INTERNAL"], Chrome does “the right thing” by skipping the device selection popup: users go straight to the fingerprint popup, with no need to select “this device”!